Reading, writing and evolution

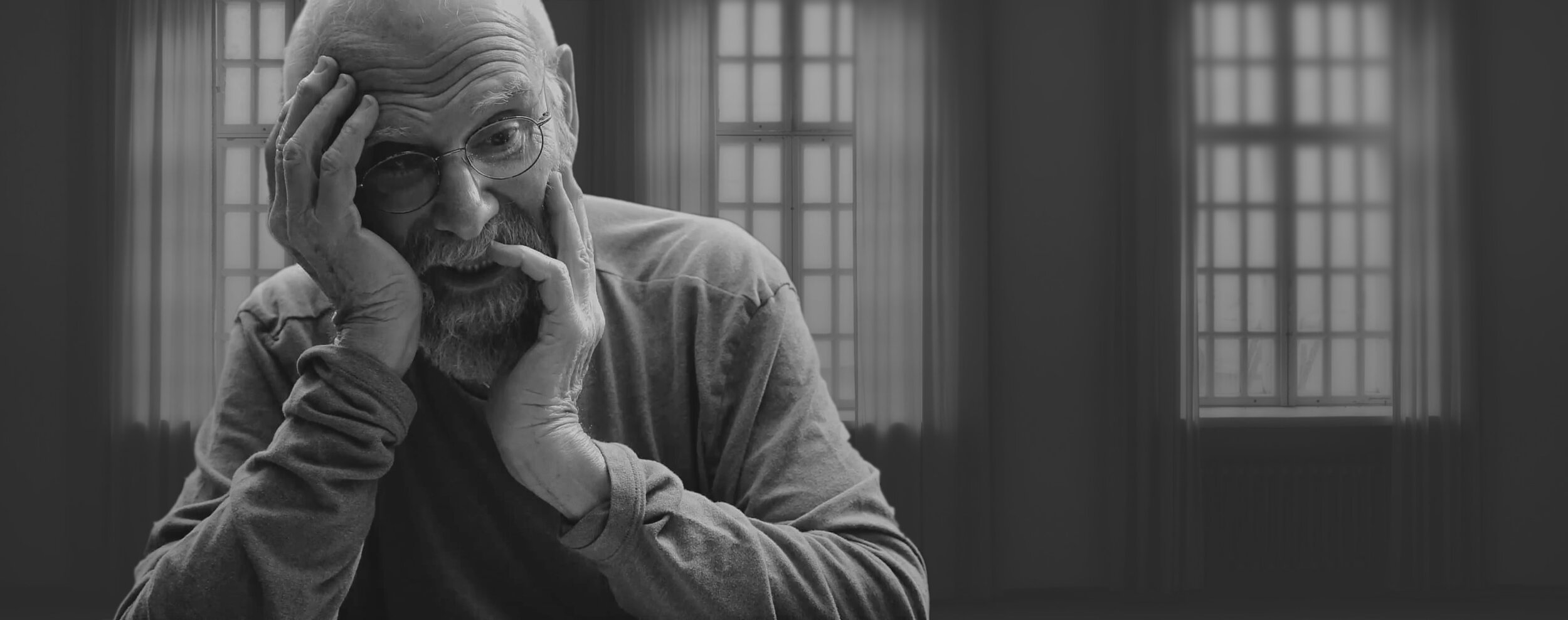

Reading and writing: do they go together like love and marriage? Well, it turns out the story is complicated. Take Howard Engel, a novelist who wrote to Dr. Sacks a few years ago. He had a stroke that suddenly destroyed, with almost surgical precision, his ability to read.

Uncannily, the stroke did not affect Howard’s ability to write at all. And (as Dr. Sacks’s subjects often do) he came up with a remarkable strategy to continue as a novelist, despite being unable to read what he has just written.

You may have seen Dr. Sacks’s essay about Howard in the New Yorker a few weeks ago, but if you missed it, fear not: the unabridged version is included in The Mind’s Eye. You can also read a little bit in July’s Footnote of the Month.

The center in our brain for understanding and producing language is uniquely human, having evolved some hundreds of thousands of years ago. But how is it that reading, a cultural invention only a few thousand years old, also has a dedicated center in the brain? If evolution didn’t put it there, what did?

We won’t give it all away here, but the answer involves a lot of your favorite characters and ideas, including Darwin and Wallace, Borges and Japanese poetry, the colorblind painter, hyperlexia, musical alexia, the evolution of alphabets, and, of course, amazingly adaptable brains.