Footnote of the Month: August 2010

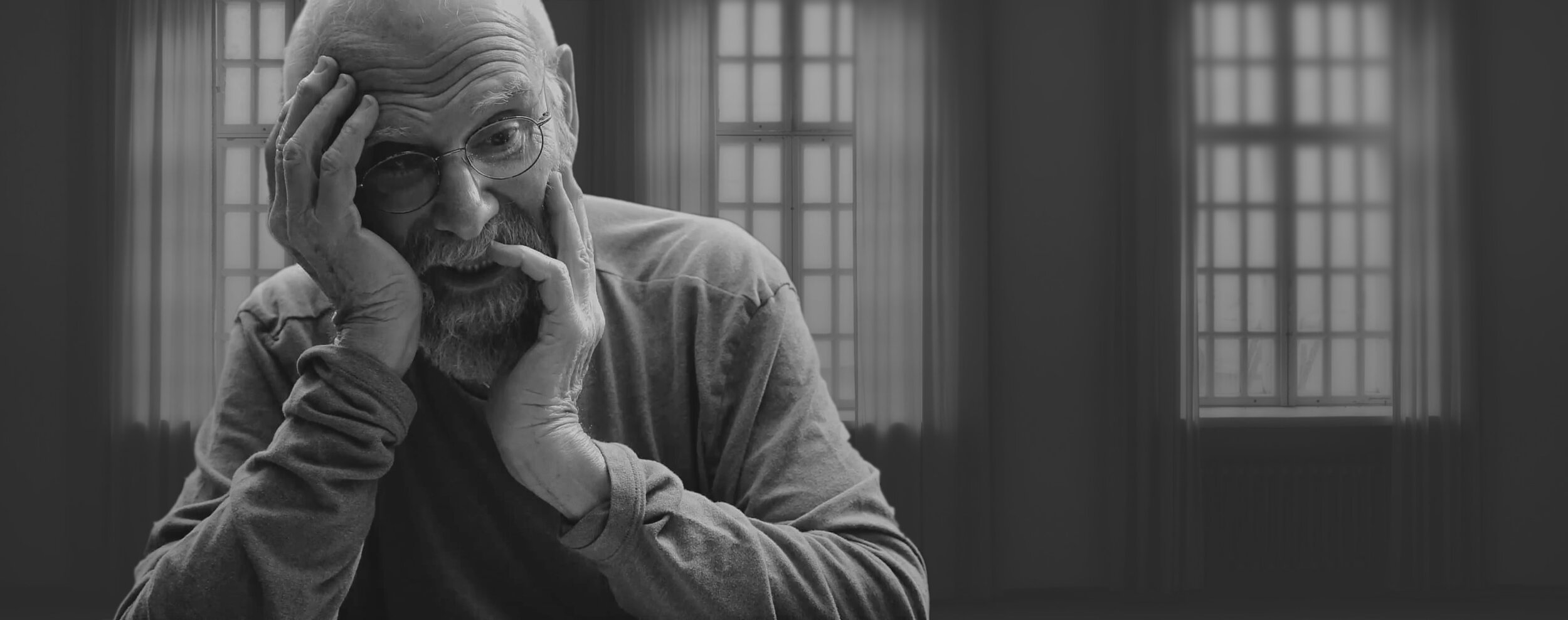

Bravo to the Mark Morris Dance Group for their pioneering program bringing music, and dance, to people with Parkinson’s disease. Dr. Sacks first saw the power of music in his Awakenings patients, survivors of the encephalitis lethargica epidemic who had an extremely severe form of parkinsonism which left them motionless, like human statues.

The power of music to integrate and cure, to liberate the parkinsonian and give him freedom while it lasts . . . is quite fundamental, and seen in every patient. This was shown beautifully, and discussed with great insight, by Edith T., a former music teacher. She said she had become “graceless” with the onset of parkinsonism, that her movements had become “wooden, mechanical—like a robot or doll,” that she had lost her former “naturalness” and “musicalness” of movement, that—in a word—she had been “unmusicked.” Fortunately, she added, the disease was “accompanied by its own cure.”

I raised an eyebrow. “Music,” she explained. “As I am unmusicked, I must be remusicked.” Often, she said, she would find herself “frozen,” utterly motionless, deprived of the power, the impulse, the thought, of any motion; she felt at such times “like a still photo, a frozen frame” . . . without substance or life. In this state, this statelessness, this timeless irreality, she would remain, motionless-helpless, until music came: “Songs, tunes I knew from years ago, catchy tunes, rhythmic tunes, the sort I loved to dance to.”

With this sudden imagining of music . . . the power of motion, action, would suddenly return, [along with a] sense of . . . restored personality and reality. Now, as Edith T. put it, she could “dance out of the frame,” the flat frozen visualness in which she was trapped, and move freely and gracefully: “It was like suddenly remembering myself, my own living tune.” But then, just as suddenly, the inner music would cease, and with this all motion and actuality would vanish, and she would fall instantly, once again, into a parkinsonian abyss.

Equally striking, and analogous, was the power of touch. At times when there was no music to come to her aid, and she would be frozen absolutely motionless in the corridor, the simplest human contact could come to the rescue. One had only to take her hand, or touch her in the lightest possible way, for her to “awaken”; one had only to walk with her and she could walk perfectly, not imitating or echoing one, but in her own way. But the moment one stopped, she would stop too.

From Awakenings, Vintage paperback edition, p. 60.